Welcome to another guest post for OWS CycCon’t Worldbuilding blog hop! Today I have for you an author of Steampunk Fairytales, and they will be talking about their process creating their fantastical worlds. You can also find a full list of authors and topics on the OWS Cycon website.

Welcome Crysta K. Coburn!

Ooooooo, Steampunk Fairytales! Please do tell, what is The Queen of Clocks and Other Steampunk Tales about?

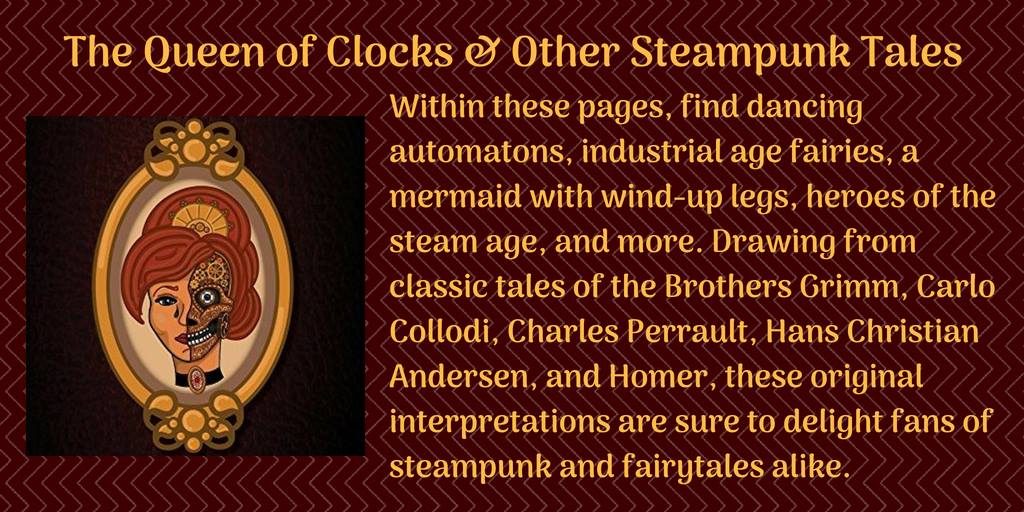

“Once upon a time” is a phrase that immediately conjures images of enchantment. Royal balls, magical creatures, love at first sight… We are taken to a fantasy world where anything is possible. The Queen of Clocks and Other Steampunk Tales brings together the magic of fairytale and the allure of cogs and gears. Within these pages, find dancing automatons, industrial age fairies, a mermaid with wind-up legs, heroes of the steam age, and more. Drawing from classic tales of the Brothers Grimm, Carlo Collodi, Charles Perrault, Hans Christian Andersen, and Homer, these original interpretations are sure to delight fans of steampunk and fairytales alike.

What are the main differences between the “regular world” and the world on the other side of your barrier?

Queen of Clocks is comprised of seven stories by seven authors (of which I am one), but we all placed our stories in the realm of fairytales—though not necessarily the same realm. Fairytales resemble a kind of idealized world of earth’s past. Of course, these are also steampunk fairytales, so we have automatons that can move and speak, which they don’t do in the “regular world.” There are also mermaids and fairies in some of the stories. One of the things I loved most about working on this book was seeing the similarities and differences between each author’s take on these two things, fairytales and steampunk.

Does language play any role in your world? Does everyone speak the same language, or is there variety? Did you invent any new slang or terminology during your world-building process?

Everyone seems to be speaking English, though a couple of stories are in fact not of English origin. The title story by Thomas Gregory explicitly takes place in Germany, so one assumes the characters are speaking German and the story has been “translated” for the reader’s benefit. Fairies and mermaids also speak English, although, especially on the part of the merfolk, there is no reason for this. That is the magic of fairytales!

What most of us have done in this anthology is take established words like “automaton” and “marionette” and given them new interpretations. A marionette is “a puppet worked from above by strings attached to its limbs.” Phoebe Darqueling has a marionette that is not only stringless, but sentient and able to move on its own. The title character in “Treasure” (my story) is called an automaton because her body is mechanical in nature, yet is able to move, dance, sing, and think for herself. In a later era—post 1921—she would probably be called a robot or android. The same for all of the sentient clockwork characters in “The Queen of Clocks.” The terminology used is limited to the “time period” of the stories.

What kinds of climates do your characters experience? Do they see a lot of change or is it always the same? Has your world always had this kind of climate, or has it changed over time?

Victoria L. Szulc’s “Sleeping Steaming Beauty” takes place in a reimagined Victorian world that is ravaged by the pollution of rapid industrialization that is enhanced by sorcery and magic. The “evil” fairy is fighting for environmental protection.

The world of “Odysseus?” by Aaron Isett is set during a technologically advanced Crimean War and takes place almost entirely on a ship at sea.

The undersea world in K. Gray’s “The Little Wind-up Mermaid” in some ways mirrors our surface world, but has its own unique culture and traditions. The surface also is reimagined with airships and other fantastical elements. One can only guess what kind of world will come out of the joining of these two worlds.

What do people in your invented world do for fun? Are there sports, games, music, or other activities they do in their free time?

The first story, “The Clockwork Nightingale” by Bess Raechel Goden revolves entirely around music. Treasure, the automaton from “Treasure,” is a dancer and singer from a traveling performance troupe. There is also a clockwork band in “The Queen of Clocks.” I don’t know how we all hit upon music for our stories, but it seems a natural fit. In “The Little Wind-up Mermaid,” it is books that most enchant.

Your Process

When you build a world, what is your process like? Do you do a lot of research upfront, wing it completely, or something in between?

Both. I tend to write a lot of fantasy because I hate getting things wrong, and in fantasy, I can do whatever I want, make up any rules I want. There are conventions to fairytales, but there is so much room to play! I have also written historical stories, whether it has fantastical elements or not, and I do a ton of research for that. I find history fascinating, and I enjoy putting in less well-known historical nods. My story “Treasure” is actually based on a little known earlier telling of “Snow White” in which Snow White is a fairy child rather than human-born.

How central is the setting of your story to the story itself? Is it more of an interesting backdrop, or is it integral to the events of the story?

I feel like with a theme such as “steampunk,” the setting is very important because that is a lot of what makes a story steampunk over, say, historical fiction or straight up fantasy. I don’t mean Victorian or England—I prefer stories that are neither—but there is an aesthetic there, and most people recognize it when they see it.

When helping the reader get to know the world you built, what techniques do you use? Do you tend to be upfront about things, or keep the reader in the dark and feed them only bits at a time?

I prefer to set the scene immediately. As a reader, I become frustrated when things are revealed piecemeal because it may not jive with what I have already created from what I was initially given in my head, and it’s hard to rebuild. It can be something as small as a character being revealed to have luscious blond hair when the entire time I was picturing them as a brunette or the fact that the setting is on a space station when for the past six chapters, I thought it was a planet. If it’s part of a big reveal, fine, but leave a trail of breadcrumbs.

How much of a role does realism and hard scientific fact play in your world-building? Do you strive for 100% accuracy, or do you leave room for the fantastical and unexplainable in your world?

I like science, and I prefer it to be 100% as accurate as possible. I don’t like making up bad science, which is part of why I steer towards the fantastical. My story “Heaven Ain’t Close” (Cosmic Encounters) takes place on Mars, and I don’t go into the tech at all. I do have a friend now who works with AIs and is very technologically knowledgeable, so I may exploit that later.

Do you have any specialized training or background from your “real life” that has informed your world-building?

The very first steampunk story that I had published (“The Waiting Future” in the steampunk erotica anthology Valves and Vixens) takes place in reimagined Meiji era Japan. I chose that setting because I have a BA in Asian Studies with an emphasis on East Asia and minored in Japanese, so I know a heck of a lot more about Japanese history than English. “Heaven Ain’t Close” is also based on Japanese history—specifically the Edo period pleasure quarters—although it takes place in the future on Mars.

I also write historical and horror fiction that take place in Michigan and surrounding areas because that is where I grew up and currently live. There isn’t a ton of stories that take place here, so I like to highlight the region. I also lived in San Francisco and surrounding Bay Area for about three years, so that gets mentioned a fair amount, too. I am always hesitant to use San Francisco in my horror fiction because Anne Rice also famously used it. But we both lived there, and I can’t help that.

How do you keep all of the details of your world and characters straight? Do you have a system for deciding on different factors and keeping it all organized, or does it live more in your head?

I take copious notes. For short stories, I don’t need a folder on my computer for every one of them, but I do keep folders for time periods and genres. Every book or series gets its own folder filled with reference photos, character descriptions, and world notes.

Did you experience any difficulties while building your world? Any facts that refused to cooperate or inconsistencies you needed to address while editing?

This is probably a weird one, but I struggled to give Treasure dialogue. In fairytales, it’s common for characters not to talk, but I realized that in a modern story, it was odd not to include some conversation. Not speaking took away Treasure’s agency.

In “The Waiting Future,” I chose not to give a character a name, which I struggled with a bit because it seemed rude not to give her a name, but at the same time, people are often not called by their names in Japan. The main character, who is telling the story, consistently refers to her as Sister, which we don’t really do in English, but is common in Japan. The other characters refer to her as “Nakamura’s wife” (or “your sister”) because there is no distinction between genders such as Mr. and Mrs. You can’t ask Mr. Nakamura how Mrs. Nakamura is because they are both Nakamura-san. Choosing how to deal with the many honorifics was difficult. In my head, I had all of the dialogue in Japanese, then translated it to English. If I didn’t know how to say it in Japanese, I didn’t write it. (Unfortunately, it’s been a few years, and I can’t easily do that anymore. Warui gakkusei desu…)

Where can people find you on the web?

Thank you so much for having me! I really enjoyed sharing these different worlds with everyone. You can find my CyCon booth here. I am on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @crystakcoburn. Find out more about my books and check out my blogs at crystakcoburn.blogspot.com.

For more stops on our World-building Showcase, visit the tour page on the OWS CyCon website. You can also find more great Sci Fi authors and books on our main Sci Fi event page.